http://dx.doi.org/10.35381/i.p.v4i1.1694

Perceptions towards teaching English as a Third Language in a Shuar Community

Percepciones hacia la enseñanza del inglés como tercer idioma en una comunidad Shuar

Cristian Lenin Salinas-Vázquez

cristian.salinas.83@est.ucacue.edu.ec

Universidad Católica de Cuenca, Cuenca, Cuenca

Ecuador

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0554-8422

Tania Alexandra Rodas-Auquilla

Universidad Católica de Cuenca, Cuenca, Cuenca

Ecuador

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6883-3047

Recibido: 15 de noviembre 2021

Revisado: 10 de diciembre 2021

Aprobado: 15 de febrero 2022

Publicado: 01 de marzo 2022

ABSTRACT

This paper aims to explore and identify the best possible way to introduce a third language into the educational curriculum in an environment where students are already bilingual. Qualitative research has been carried out in a specific school to discover the challenges of their language education. According to the findings, students claim to have several difficulties in learning English. Once all the data was analyzed, the second step was to create material to support third language acquisition. The first step is to recognize the importance of English, and the next is to introduce the language in the students' own context and, finally, to consolidate knowledge of the language. This will provide teachers with methods and techniques for a third language acquisition class.

Descriptors: Student projects; verbal learning; learning methods. (UNESCO Thesaurus).

El presente trabajo tiene como objetivo explorar e identificar la mejor manera posible de introducir una tercera lengua en el currículo educativo en un entorno donde los estudiantes ya son bilingües. Se ha llevado a cabo una investigación cualitativa en una escuela específica para descubrir los desafíos de su educación en idiomas. Según los hallazgos, los estudiantes afirman tener varias dificultades para aprender inglés. Una vez que se analizaron todos los datos, el segundo paso fue crear material para apoyar la adquisición de un tercer idioma. El primer paso es reconocer la importancia del inglés, y el siguiente es introducir el idioma en el propio contexto de los estudiantes y, finalmente, consolidar el conocimiento del idioma. Esto proporcionará a los maestros métodos y técnicas para una clase de adquisición de un tercer idioma.

Descriptores: Proyecto del alumno; aprendizaje verbal; método de aprendizaje. (Tesauro UNESCO).

INTRODUCTION

Ecuador is a unique country, not only because of its exceptional geographical wonders, but also on account of its people and culture. According to the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA, 2021), the current population of Ecuador is almost 17.5 million including 14 indigenous nationalities that altogether number more than 1 million people and are grouped into many local, regional and national organizations. Each nationality has its own native language.

The main language spoken in Ecuador is Spanish, but there are several other languages related to the indigenous communities. The most common indigenous languages spoken in the country are Kichwa and Shuar, which are both used for intercultural communication. These languages are so important for the country and its culture that they are included in the so-called Model of Bilingual Intercultural Educational System (Modelo del Sistema de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe or MOSEIB in Spanish). This model is based on the concept that Ecuador is a multilingual and multinational country with the following nationalities: Awa, Epera, Chachi, Tsa'chi, Kichwa, A'i (Cofán), Pai (Secoya), Bai (Siona), Wao, Achuar, Shiwiar, Shuar, Sapara, and Andwa. Each nationality has the constitutional right to run its own educational system.

The nationalities mentioned above today coexist with the descendants of ancient cultures, such as Valdivia, Huancavilca, Manta, Yumbo, as well as present day Afro-Ecuadorians, Montubios, and Mestizos (Ministerio de Educación del Ecuador,2014). As a result of its history and cultural heritage, a number of Ecuadorian communities are already bilingual. This means that their ancestral language is their mother tongue or first language (L1). Spanish functions as a lingua franca which, in indigenous contexts, is a second language (L2). English then, for many indigenous speakers is an additional or third language (L3). This is in line with what (Cabrelli & Iverson, 2018) describe, namely, that third language acquisition is common in multilingual contexts where two or more languages are used alongside each other.

For the purposes of this article, third language acquisition was examined in an educational institution in the town of San Juan Bosco, where students are of Mestizo and Shuar origin. The majority of the students identify themselves as Mestizos with Spanish being their first language. About one-quarter of the learners surveyed speak Shuar as their mother tongue (L1), therefore, Spanish is considered a second language (L2) for them. In this context, English is either an L2 or an L3, depending on the learners’ mother tongue.

This paper aims to shed light on the students’ perceptions related to the teachers’ practices in a multilingual environment, where the lack of a common mother tongue (L1) poses challenges. The research study itself focuses on perceptions towards teaching English as a third language (L3) in a Shuar community. The main objective was to engage in a cross-cultural dialogue through participation in order to find out how difficult or easy it is to learn a third language.

More specifically, the study focuses on the students’ perceptions and experiences and aims at examining if learning a third language is easier or more difficult for those participants for whom English constitutes a third language. Furthermore, the aim was to explore if students’ mother tongue and L2 play a positive or negative role in the context of teaching and learning a third language (as perceived by the participants whose mother tongue is Shuar).

(Haboud, 2009) investigates the complexity of linguistic contact, which entails ethnic disputes and social imbalance, and she emphasizes the necessity of the development of a perspective that recognizes both diglossia and bilingualism in other words, one that makes an effort to comprehend not just the context of language usage, but also the social consequences that might be involved. Therefore, the present study considers not only the linguistic aspects but also the social, political, and geographic situation in order to obtain results that might be most relevant as well as have a level of validity that can be expected of a case-study type design.

The third language to be analyzed is English since it has become highly relevant in these times of globalization and international communication. Nowadays, English is considered a global language for the purposes of global communication. As has been mentioned above, in Ecuador Spanish is used as a lingua franca, but the acquisition of a third language, in this case, English, will help students have more opportunities in life. For (Jessner & Cenoz, 2007), English is classified as a foreign language with no official status in many countries around the world, yet it is becoming more widely used as a means of communication. That is why the present study may result in obtaining useful information regarding the acquisition of English as a third language for those who are already bilingual.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Multilingualism

The study of third language acquisition is a relatively new area of research, but in recent years there have been several books and articles on the subject. A common feature of the academic output regarding the subject is that the authors writing about this subject combine the issue of learning a third language with the wider topic of multilingualism. For example, the authors in (Pinto & Alexandre, 2021) look at the role of multilingual teachers and how they follow approaches that seem to work well in plurilingual contexts. Part III of the book contains studies that look at individual learning strategies including such topics as motivation and attitudes, and how monolingual bias in the classroom should be avoided. In order to accomplish third language learning in a successful way, the role of the teacher is fundamental.

First of all, the teacher must be trilingual or multilingual and must be prepared to play the role of the tutor. What does that mean? It means that it does not only require the teacher to be trilingual or multilingual. He or she must also have the required qualifications in all the languages and have deep knowledge of the grammatical system of the languages involved. The teacher must be prepared to answer questions related to the differences and similarities between languages. The teacher must also be aware of the background of the students so that he or she can guide them throughout the learning process.

Some authors state that this approach initiates a process in which all languages may take on the role of ‘bridge languages’, and assume different functions according to the specific needs of the speaker (Pinto et al. 2021). Ultimately, each language is going to play an important role in the speaker’s life and will converge together to accomplish the final goal, which is to create the conditions for successful communication among the interlocutors.

Third language acquisition

What might be the best age for the introduction of a third language? A recently published book on research into how third or additional languages are learned (Bardel & Sánchez, 2020) contains two theoretical chapters and six empirical studies. All of them discuss issues that are highly relevant for the present case study, and the authors of each chapter emphasize that multilingual language learning is a complex process. The authors of the edited volume highlight the importance of such factors as the age when the additional language is introduced, social and affective factors, quality of instruction, the typology of the languages already spoken, and what role the latter factor plays in the acquisition of the vocabulary and syntax of the third language, (Sánchez, 2020) emphasizes that older learners and late starters have an apparent superiority over younger learners and early starters.

Cross-linguistic influence in third language acquisition

Another author who is relevant for the topic discussed in this article is (Cenoz, 2003) owing to her contribution to the study of the cross-linguistic influence on third language (L3) acquisition. She explains that acquisition is potentially more complex than cross-linguistic influence in the second language (L2) acquisition because third language acquisition involves all the processes associated with second language acquisition as well as the unique and potentially more complex relationships that evolve among the languages known or being acquired by the learner.

Linguistic awareness in multi-lingual

Another author (Jessner, 2006) proposes that crosslinguistic awareness is the ability of multilinguals to make implicit or explicit use of the connections and the overlapping that exist between the different language systems in the human brain during language production and use. This is to say that for those who are already bilingual it may be easier to acquire a third or fourth language since some acquisition techniques could already be implanted in their brains.

The knowledge of the learning process of the previous languages will bring about an advantage in the acquisition of a new language. In a pertinent study (Cenoz, 2021) suggests that learning a second language can be compared to learning how to drive a car, while learning a third language could be perceived as learning how to drive a bus. The strategies and skills involved in driving a car can be very useful when driving another type of vehicle. The experience embedded in previous knowledge can complement the new one.

A relevant study looks at how learners whose first language is Croatian and who are learning English as a second language acquire Spanish as an additional language (L3). (Perić & Novak-Mijić (2018), focus on lexical errors and lexical transfer. They conclude that English (L2 in the context investigated) is the main source of transfer but they also find that lexical errors decrease in number as proficiency in the additional language increases (p. 91). To avoid those errors, the techniques and educational strategies used by the teacher must be appropriate. Teachers must consider and treat as an advantage their students’ bilingualism and the way they acquired those two languages can guide them in creating the means for the successful acquisition of a third language.

Minority languages

(Cenoz & Durk, 2019), investigate the relationship between minority languages and national state languages. In the authors’ view, teaching minority languages necessarily implies the need for bilingual education. The aim is not to replace the majority language, but for both the minority and the majority language to thrive. With English also appearing as an additional language, the promotion of multilingualism is an important educational goal in the Basque Country and Friesland, whose language teaching/learning practices the article examines.

The importance of minority languages has recently increased in Ecuador and this provides an advantage to those who, over and above the majority language, namely Spanish, can speak their native language, too. The government acknowledges the importance of preserving ancestral languages and this has led to the creation of a system of bilingual schools (Ministerio de Educación, 2014). Just like in the Basque Country and Friesland, English has been added to the Ecuadorian curriculum, and for many indigenous students, this implies that they are expected to learn an additional (namely, third) language.

In this case study, the aim is to investigate perceptions towards learning English as a third language in a Shuar Community and, beyond that, how having learnt a second language (L2) may help or hinder the learning of a third language (L3). More importantly, the aim is to explore if the activation of previous linguistic knowledge can influence the learning of a third language. The crux of the matter is to establish if knowing two languages makes the learning of a third language easier or not. Since the present article is a case study, whose generalizability is necessarily limited, an attempt has been made to gauge the perceptions of a limited number of learners concerning how third languages are learnt and taught.

Study type

The case study presented in this article represents a type of qualitative research, (Allen, 2017) states that the purpose of qualitative research is to generate knowledge and create understanding about the social world. The data gathering involved a questionnaire that contained only questions.

The author first sought permission from the school’s principal and requested signed consent forms from the students’ parents and the students themselves. Informed consent was given after the author held a meeting with the parents where the topic, the research objectives, and the instruments were presented.

The questionnaire administered to the students had the aim of gauging students’ perceptions of learning an additional language, namely, English (a first additional language for Mestizo students and a second additional language for Shuar students).

The questions in the survey were intended to explore the students’ use of their mother tongue, their perceptions of the use of the home language, and their attitudes to languages in general. The data gathering took place at a high school called Unidad Educativa “Milenio Nueva Generación” located in the town of San Juan Bosco in Morona Santiago province.

Participants

The research involved 35 students, who were 15 years old at the time of the survey. The distribution according to sex was fairly balanced since the sample consisted of 20 female and 15 male students. Eight students of the 35 respondents speak Shuar as their mother tongue (L1), while 27 identify as Mestizos, whose native language (L1) is Spanish.

Data collection

A reliability analysis was performed with Cronbach's Alpha coefficient, which obtained a very good value of 0.936. The results were processed with the SPSS 25 program (Field, 2017). Because of working with ordinal variables of two groups (Shuar and Mestizo) with different numbers of members, it was decided to use error bar diagrams that present the average accompanied by a bar whose size reflects the variability of criteria of the students. The size of the error bars implies the variability that exists in the opinions of the students. In some cases, tables with the average accompanied by the standard deviation (SD) are used. The standard deviation, as well as the error bar, show the variability of criteria that are gathered in an average. Thus, if a bar or SD is small, it is assumed that the members of the group (Shuar or Mestizos) have similar criteria on an evaluated item, otherwise, it is assumed that they have different criteria.

RESULTS

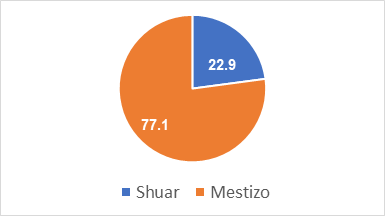

The results are organized into three sections; the first has to do with the intercultural perception and valuation of the language. The second section deals with the teaching of English and the use of this language outside the classroom. Finally, the third section presents data on the influence of the mother tongue on the learning of English as a second and third language. All the results are presented in comparative form between the Shuar and the Mestizos (although without expressing the levels of probability due to the small sample of the Shuar group). 22.9% of the students are Shuar and the rest are Mestizos as displayed in the following figure.

Figure 1. Sector diagram of the students’ ethnic group.

Source: Elaborated by the author.

Before the presentation of the opinion of these two groups, it is important to mention that the main difference between the Shuar and the Mestizo students is that the latter only speak Spanish. Almost 100% of the participants who were born in bilingual homes were Spanish and their parents’ mothers tongue is spoken at the same time. They speak Shuar in their homes and learn Spanish at school, and in eighth grade started learning English as a foreign language for five hours a week.

Students’ profile

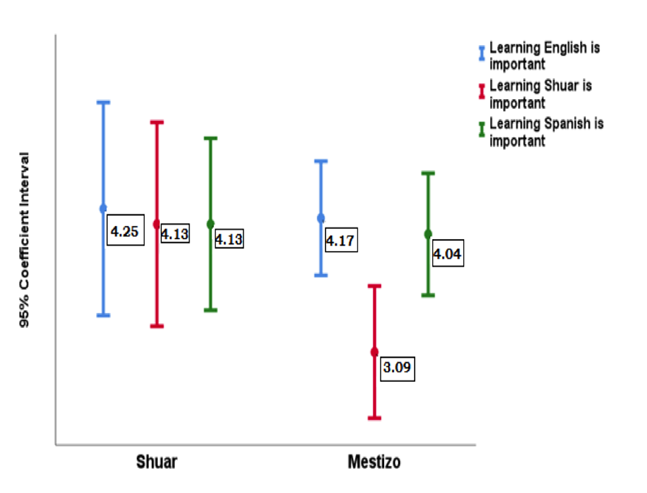

To answer the question of how difficult or easy it is to learn a third language, we inquired about the level of integration and the importance they give to learning a language. Figure 2 shows the students' evaluation of their mother tongue, the Shuar language and the English language. In the Shuar group, it can be seen that they agree with a similar evaluation of the three languages (around 4.25). However, in the group of Mestizo students, it is observed that there is an undervaluation of the Shuar language (whose average oscillates around 3.09), while the English and Spanish languages have a value with which they correlate. The Mestizos reflect this particularity at a general level in the cultural evaluation of the Shuar people.

Figure 2. Error bars diagram of the student's opinion about the importance of learning a language.

Source: Elaborated by the author.

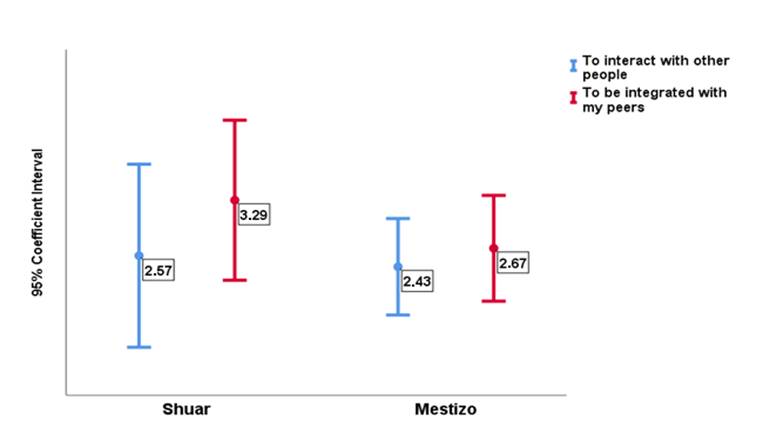

Figure 3 shows that there are differences between the Mestizos and the Shuar with respect to the difficulties that their mother tongue causes them in their intercultural relations. Shuar and Mestizos attribute the difficulty in interacting with other people to their mother tongue (about 2.57 times as many as neither agree nor disagree). However, in terms of integration with peers, the Shuar agree that their mother tongue prevents them from integrating easily (average of 3.29).

Figure 3. Error bars diagram of the student's opinion about the difficulties caused by their mother tongue.

Source: Elaborated by the autor.

Students’ opinions about teaching

To evaluate the perceptions regarding the teaching of English as a third language in a Shuar community, Table 1 is presented. When students were asked to evaluate the teaching process in the institution and the role of the teacher, similar opinions were found among Shuar and Mestizo students with respect to the institution, but not with respect to teachers. The results of the averages with their respective standard deviation (SD) are shown in Table 1. Both groups agree that teaching focuses mainly on context and intercultural relations, with averages above 3.57, while they present a lower tendency with respect to the purpose of teaching English based on grammar or communication (average ratings of around 3.42).

Regarding their evaluation of the teacher, it was found that the Mestizo students believe that they are encouraged to learn English more than the Shuar (average of 3.74), as well as expect teachers to offer correction in an appropriate manner (average of 4.04). However, it is the Shuar who indicates that teachers are concerned about explaining terms using the students' native language (mean 3.88), as well as offering appropriate feedback (mean 3.75). In terms of language use, Mestizo students are more in agreement with the fact of using the Spanish language (with an average of 3.08) compared to students from the Shuar community (whose average is 2.75). Regarding the criterion of not having a sufficient level to use the language in students, this is slightly more marked in the Shuar students (average of 2.75) than in the Mestizo students (average of 2.43).

Table 1.

Students’ opinion about teaching, teacher and use the English language.

|

|

Shuar |

|

Mestizos |

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

|

M |

SD |

|

The Teaching of English at their school focuses on... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Grammar |

3.38 |

0.92 |

|

3.43 |

1.24 |

|

Communication |

3.57 |

1.13 |

|

3.42 |

1.14 |

|

Context (provides examples from the student's experience) |

3.63 |

0.92 |

|

3.62 |

1.12 |

|

Intercultural relations (history, worldview, traditions, etc.) |

3.38 |

1.06 |

|

3.55 |

1.22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In terms of motivation, the teacher... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Encourages students to learn English |

3.50 |

1.41 |

|

3.74 |

1.16 |

|

Uses the students' native language to explain a term |

3.88 |

0.64 |

|

3.50 |

1.10 |

|

Correct students in an appropriate manner |

3.75 |

1.28 |

|

4.04 |

0.86 |

|

Provides appropriate feedback |

3.75 |

0.89 |

|

3.35 |

1.19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How much do they use the language outside of class... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I practice on my own |

2.75 |

1.17 |

|

3.08 |

1.33 |

|

I have no level to use this language |

2.75 |

1.04 |

|

2.43 |

1.16 |

Source: Elaborated by the author.

Influence of a second language on a third language

In order to establish the influence of students' mother tongue and second language on a third language, this section of results is presented in Table 2 and Figures 4-5. When asked how the mother tongue has helped them in their learning of English, similar results were found between the two ethnic groups, which can be seen in Table 2. At a general level, Shuar students consider that there is a greater opportunity to learn English from their mother tongue (average of 3.60) compared to Mestizo students (3.04).

In terms of comprehension, listening, and reading skills, there are no differences between the two groups, and it is observed that they somewhat agree that their mother tongue has favored them (with an average of around 3.10). However, regarding speaking, it is observed that the Mestizo students are much more satisfied than the Shuar with an average of 3.16 and 2.50 respectively. Finally, it is the Shuar students who claim to have been favored by their mother tongue in their ability to write (average of 3.29) compared to the Mestizo students (average of 3.0).

Table 2.

Students’ opinion about how their mother tongues have helped them to learn English.

|

|

Shuar |

|

Mestizos |

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

|

M |

SD |

|

Mother tongue has helped them... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Learn English |

3.60 |

1.52 |

|

3.04 |

1.40 |

|

Understand better (semantics) |

3.00 |

1.41 |

|

2.94 |

1.29 |

|

Listen to spoken English better (listening) |

3.14 |

1.46 |

|

3.26 |

1.28 |

|

Speak English better (speaking) |

2.50 |

1.60 |

|

3.16 |

1.43 |

|

Writ better (writing) |

3.29 |

1.60 |

|

3.00 |

1.28 |

|

Read better (reading) |

3.14 |

1.46 |

|

3.20 |

1.28 |

Source: Elaborated by the author.

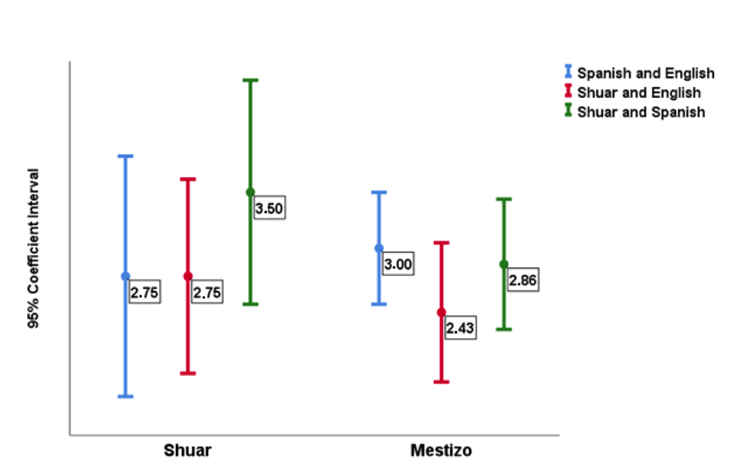

Figure 4 shows the average opinion of the students about the similarity between languages. Apart from one case, students show similarity in their criteria; however, there are slight differences among them. For example, the Shuar believe that Spanish is less similar to English and instead assume that Shuar is more like Spanish. In the latter case, the average of the Shuar reached a value of 3.50 and Mestizos 2.86. This is probably, as (Heredia-Arboleda et al. 2020) say, due to the fact that the Shuar display the characteristics of language interference. Another criterion, although not very marked in the difference, has to do with the perception that Shuar is similar to English, something that the Shuar students themselves believe more than the Mestizos.

Figure 4. Error bars diagram of the student's opinion about the similarity of the languages.

Source: Elaborated by the author.

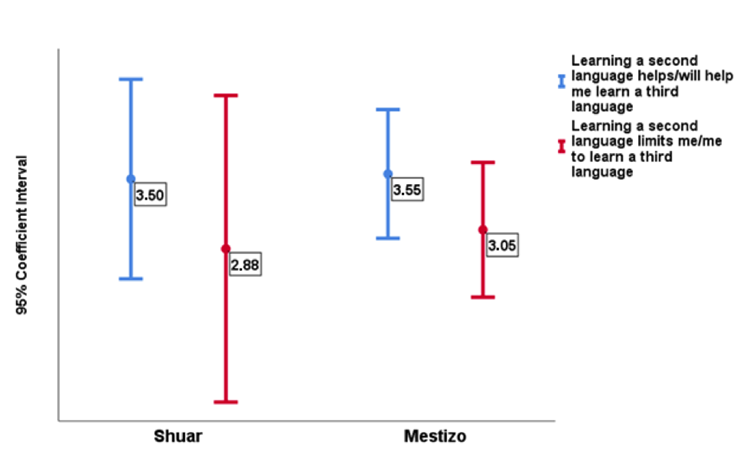

The results concerning the influence of a second language on a third language shows very similar results between the two groups (Figure 5). However, it is important to mention that the only ones who have a second language and are learning a third language are the Shuar students. The average reported for the help provided by the second in the third language is 3.50, while the average for the difficulty provided by the second in the third language does not reach 3. It is very important to note that the criterion on the help of a second language to learn a third language is somehow shared by the group of Shuar students, however, this is not the case concerning the difficulties. In this case, the error bar is very large, which indicates that they do not agree among themselves that Spanish is a limitation for learning English.

Figure 5. Error bars diagram of the students’ opinion about the influence of a second language on a third language.

Source: Elaborated by the autor.

PROPOSAL

The final aim of this paper is to obtain sufficient data, and backup information to acknowledge the upsides and downsides of introducing a third language in an environment where students are bilingual and where the gap within a majority language in this case, Spanish and minority languages in this case Shuar is big enough to the point that the last one is facing extinction. The data obtained may help to deal with the weaker points when talking about education and language acquisition. Once all the data is processed, the development, and hopefully the application of the proposal will help the students and teachers of the Unidad Educativa del Milenio Nueva Generación.

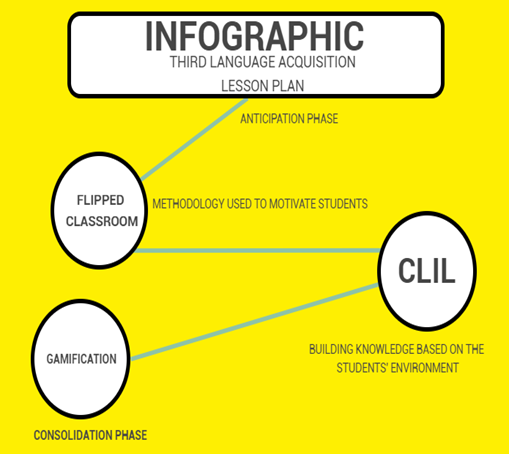

Figure 6. Proposal to create a lesson plan for teaching English as a Second or Third language.

Source: Elaborated by the autor.

The main aim of this proposal is to create a lesson plan that will be a complement to the Ecuadorian curriculum in order to allow for effective third language acquisition, namely, the guide called Modelo del Sistema de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe [Model of Bilingual Intercultural Educational System]. Nevertheless, one must consider that Ecuador is a multicultural country, and a piece of research cannot involve and help every single one of those cultures. The hope is that the creation of the present one will help specifically this educational unit. Such a lesson plan will focus on the needs of the students by considering not only their already spoken languages, but also their social, geographical, economic and political background. This will focus on improving the learning process in a way that is consistent with their context. Students must be able to use all three languages without lacking knowledge or context.

This will help teachers to deal with the challenges of working with third language-speaking students. Teachers nowadays are facing many struggles related to language acquisition. This lesson plan will assist and support them to face such challenges and, in the end, will be able to support the students and the community itself. It will focus on certain strategies that the teacher can apply in class. It will also provide specific activities to improve the learning process including activities where students will use all L1, L2, and L3. These activities will help enhance all of the four skills, namely, reading, listening, speaking, and writing. Meant to produce the language.

Teaching Methods

Flipped classroom: The implementation of the flipped classroom is relevant since technology has become an integral part of teaching now that the pandemic has forced this option to be made available to more students and teachers (Fuchs, 2021). This innovative method changes the roles of the teacher and the students. Now the classroom is not the place to acquire information but the place to perform activities and apply the knowledge. The teacher in this setup becomes just a guide to help students use that knowledge.

This method will anticipate the importance of English (Sakulprasertsri et al. 2017), have explained that the concept underlying the flipped learning approach includes helping students to become active learners and enhance their engagement. The value of this approach is to release class time for learning activities or workshops where students can inquire about the content, test their skills in applying knowledge, and interact with one another in hands-on activities. The method is both effective and motivating for language learners, too.

CLIL: In order to create this lesson plan, CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) will be one of the methodologies to follow. But what is CLIL? It is one growing teaching approach within bilingual education. The purpose of this methodology is to integrate language into the learning of other subjects such as Mathematics, History, Science, etc. According to (Gabillon, 2020), CLIL is not only about using an additional language (e.g., foreign, autochthonous, heritage, second language) as a medium to teach subject content.

The approach aims to build and reinforce learners’ knowledge of other disciplines while using the language to solve problems and develop critical thinking. In this context, CLIL will help to connect and later produce the language in the students’ own context, because it will not only focus on language and grammar but will integrate different disciplines into the learning process creating an ideal confluence of the languages.

Gamification: Gamification will play a crucial role in this guide since several of the activities will be based on it. Having an active class is not only when students participate but when they also enjoy the process and for this reason this methodology is considered highly appropriate. (Seaborn & Fels, 2015) have pointed out that gamification is a multidisciplinary concept spanning a range of theoretical and empirical knowledge, technological domains, and platforms and is driven by an array of practical motivations. In the same way as (Subhash & Cudney, 2018) have explained, these interactive learning environments present the opportunity to enhance the teaching process through the incorporation of game elements that have been shown to capture user attention, motivate towards goals, and promote competition, effective teamwork, and communication in the class.

That is the proposal and final aim of this paper. Namely, adapting lessons to support students and teachers in the process of third language acquisition and focusing on the most suitable methods possible to accomplish the final objective, which is the production of language.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study provides some data which suggests that there is a general lack of information related to third language acquisition. Beyond that, there has been no research as yet that has explored the issue of how language acquisition affects learners for whom English is a second language (Mestizos) and for whom it is a third language (Shuar learners). The school in which this study took place is not prepared to introduce a third language into the curriculum in an efficient way. The aim of this study was to look for the student’s perceptions on the strong and weak points of language learning and teaching so that the process can be improved. Several issues have come to light and this is why some suggestions have been made above so that the shortcomings can be eliminated. The hope is that the employment of the proposals may lead to improved learning and teaching approaches and will help both the school where the research was carried out and the community at large, too.

The case study itself can provide a basis for future studies since one can be assumed that the problem outlined here is one that concerns the whole of Ecuadorian society. The lack of good results related to language acquisition is not only happening in Unidad Educativa “Milenio Nueva Generación” located in the town of San Juan Bosco in Morona Santiago province. One can assume that it might well be happening in all those bilingual schools located elsewhere, namely the coastal region, the Andean region, and the Amazonian region where Indigenous languages are still relevant for education, and where English language teaching has become compulsory,

Talking about indigenous issues is extremely delicate and complicated and can trigger a conflicting thought. So far there has not been sufficient research into exploring how teaching English as a third language can be incorporated into a curriculum for a bilingual context. The discussion needs to be based on the notion that everyone has the right to bring their culture, traditions, and customs to the classroom. This implies that everyone must be allowed to retain their social and cultural identity and learning a third language should be perceived as an opportunity supported by learners’ first and second languages.

FINANCING

No monetary assistance was involved in the project.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

To the Universidad Católica de Cuencas; for motivating the development of research.

REFERENCES CONSULTED

Allen, M. (2017). The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods (1-4). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc doi: 10.4135/9781483381411

Bardel, C., & Sánchez, L. (Eds.). (2020). Third language acquisition: Age, proficiency, and multilingualism. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Cabrelli, J., & Iverson, M. (2018). Third language acquisition. In K. Geeslin (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of Spanish linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 737-757.

Cenoz, J. (2003). Cross-linguistic influence in third language acquisition: Implications for the organization of the multilingual mental lexicon. Bulletin VALS/ASLA, 78,1-11.

Cenoz, J. (2021). Research on third language acquisition. https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/multilingual-practices/0/steps/22659

Cenoz, J., & Durk, G. (2019). Minority languages, national state languages and English in Europe: Multilingual education in the Basque Country and Friesland. Journal of Multilingual Education Research, 9(1), 61-77.

Field, A. (2017). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). London, England: SAGE Publications.

Fuchs, K. (2021). Book review: The flipped classroom—practice and practices in higher education. Frontiers in Education, 6, 307. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.741656

Gabillon, Z. (2020). Revisiting CLIL: Background, Pedagogy, and Theoretical Underpinnings. Contextes et Didactiques, (15). doi: 10.4000/ced.1836

Haboud, M. (2009). Teaching foreign languages: A challenge to Ecuadorian bilingual intercultural education. International Journal of English Studies, 9(1), 63-80.

Heredia-Arboleda, E. E., Egas Villafuerte, V. P., Reinoso Espinosa, A. G., & Obregon Mayorga, Á. P. (2020). The perceptions of indigenous students towards the occidental educational system of the English class: A study in an Ecuadorian Public University. Boletain Redepe, 9(1), 155–163. doi.org/10.36260/rbr.v9i1.904

IWGIA. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. The Indigenous world 2021: Ecuador. https://www.iwgia.org/en/

Jessner, U. (2006). Linguistic awareness in multilinguals: English as a third language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Jessner, U., & Cenoz, J. (2007). Teaching English as a third language. In International handbook of English language teaching, 15, 155-167. Boston, MA: Springer US. doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46301-8_12

Ministerio de Educación del Ecuador [Ministry of Education, Ecuador] (2014). Modelo del Sistema de Educación Intercultural Bilingüe [Model of Bilingual Intercultural Educational System]. https://www.educacionbilingue.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/MOSEIB.pdf

Perić, B., & Novak-Mijić, S. (2018). Cross-linguistic influences in L3 Spanish and the Relationship between Language Proficiency and Type of Lexical Errors. Croatian Journal of Education, 19, 91-107. doi:10.15516/cje.v19i0.2619

Pinto, J., & Alexandre, N. (2021). Multilingualism and third language acquisition: Learning and teaching trends. Berlin: Language Science Press. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4449726

Pinto, J., Alexandre, N., Ghiselli, S., Zhou, C., Freitas, M. J., Castelo, A., Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2021). Multilingualism and third language acquisition. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Sakulprasertsri, Kriengkrai & Vibulphol, Jutarat. (2017). Effects of English instruction using the flipped learning approach on English oral communication ability and motivation in English learning of upper secondary school students. Bangkok, Thailand: M. Ed. Chulalongkorn University.

Sánchez, L. (2020). Multilingualism from a language acquisition perspective. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.4138735

Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. I. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human Computer Studies, 74, 14–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.006.

Subhash, S., & Cudney, E. (2018). Gamified learning in higher education: A systematic review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior. 87, 192–206. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.028.

©2022 por los autores. Este artículo es de acceso abierto y distribuido según los términos y condiciones de la licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).