http://dx.doi.org/10.35381/i.p.v4i1.1693

Project-based learning and speech sub-skills for student motivation

Aprendizaje basado en proyectos y sub destrezas del habla para la motivación de estudiantes

Juana Guillermina Sotamba-Romero

juana.sotamba.62@est.ucacue.ed.ec

Universidad Católica de Cuenca, Cuenca, Cuenca

Ecuador

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3875-2171

Tammy Fajardo-Dack

Universidad Católica de Cuenca, Cuenca, Cuenca

Ecuador

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9330-4622

Recibido: 15 de noviembre 2021

Revisado: 10 de diciembre 2021

Aprobado: 15 de febrero 2022

Publicado: 01 de marzo 2022

ABSTRACT

The objectives were, first, to explore the sub-skills of speaking that students practice through PBL. Second, to analyze students' and teachers' perceptions of its use to enhance motivation. Twenty-seven high school students participated in the study. To obtain data, students were surveyed and their final products were evaluated through a rubric to assess fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. The results indicated that the PBA helped students practice the sub-skills of speaking. Although the students said in the interviews that they improved fluency, the results of the artifact assessment did not show this sub-skill as the highest. In terms of students' motivation, they felt they were more engaged to work on projects.

Descriptors: Educational projects; language instruction; student projects. (UNESCO Thesaurus).

RESUMEN

Los objetivos fueron, en primer lugar, explorar las sub-habilidades del habla que los estudiantes practican a través del ABP. En segundo lugar, analizar las percepciones de alumnos y profesores sobre su uso para aumentar la motivación. Veintisiete estudiantes de secundaria participaron en el estudio. Para obtener datos, se realizaron encuestas a los estudiantes y se evaluaron sus productos finales a través de una rúbrica para evaluar la fluidez, la pronunciación, el vocabulario y la gramática. Los resultados indicaron que el ABP ayudó a los estudiantes a practicar las sub-habilidades de hablar. Si bien los estudiantes dijeron en las entrevistas que mejoraron la fluidez, los resultados de la evaluación del artefacto no muestran esta sub-destreza como la más alta. En cuanto a la motivación de los estudiantes, sintieron que estaban más comprometidos para trabajar en proyectos.

Descriptores: Proyecto de educación; enseñanza de idiomas; proyecto del alumno. (Tesauro UNESCO).

INTRODUCTION

In a globalized world, English has become one of the most used languages around the world and it is necessary to rethink the proper methods and approaches teachers should use to help students acquire the language (Pucher et al. 2002). Furthermore, the aim of learning a language is to be able to communicate with other people in real contexts.

As (Krashen, 1982) argues in his Acquisition-Learning hypothesis, language acquisition is more important than language learning, and speakers should not focus on the form of their statements, but on communicative performance. In the Ecuadorian context, the national guidelines given by the Ministry of Education (Ministerio de Educación, 2014) regarding secondary students’ exit profile on oral proficiency level claims that students need to be able to “have a repertoire of language which enables them to explain the main points in an idea or problem with reasonable precision” (p. 23).

In other words, PBL allows students to foster the practice of speaking sub-skills since they have to solve a real-life problem. There is evidence of research on Project-Based Learning applied favorably to improve oral performance since students display real-context products. Thus, aside from improving communication skills, the students develop working collaboratively (Bartscher et al. 1995; Hernández & Arturo, 2019; Yaman, 2014). PBL is one of the approaches that allow students to improve their speaking skills because students are focused on their performance, not on accuracy (Jaramillo, 2019).

Students’ motivation is relevant for acquiring a new language in the current context of globalization. Although it depends on students’ contexts and beliefs, there is a close and important relationship between motivation and language acquisition (Strong, 1984). Motivation depends on different factors such as context, teachers, and on methods or approaches used to teach English as a Foreign Language (EFL). According to (Shabaan & Ghaith, 2008), intrinsic motivation is directly related to learning English as a Foreign Language. This means that being successful in acquiring a foreign language not only depends on external factors, but also on students’ internal motivation

The studies mentioned above have clearly established the aim of Project-Based Learning in motivation and improving speaking skills, they have not addressed the use of Project-Based Learning mainly for the sake of practicing speaking sub-skills and increasing motivation at the same time. Considering the critical issues, the present research aims firstly to explore the speaking sub-skills that students practice through Project-Based Learning and secondly to analyze the perceptions of both secondary students and teachers regarding the use of Project-Based Learning to increase motivation.

Theoretical framework

Project-Based Learning

PBL is a student-centered approach that challenges learners to make a project and present a final product. It involves teamwork, develops autonomous learning, creativity, and self-confidence (Poonpon, 2017), (Teague, 2000) defines PBL as an instructional approach whose aim is to allow students to construct their own knowledge going from theory to practice through authentic tasks.

Origin, main features, and challenges of Project-Based Learning

According to (Knoll, 1997) using projects as an educational tool in schools first arose as an educational movement in engineering and architecture back in the 1960s in Italy as a way to improve workers’ performance in those areas. Dewey says that PBL was influenced by the constructivism theory which sustains that knowledge should be constructed through interaction with others and empirically (as cited in Teague, 2000). Project-Based Learning is aligned with the Communicative Language Teaching approaches (CLT) which aim is similar to PBL in the sense that in CLT learners are getting ready to use language in the real world, and this can be achieved by using authentic activities that help students to develop the four main language skills (Parrish, 2019; Canale & Swain, 1980).

According to (Leat, 2017), the main feature of PBL is setting the student at the center of the teaching-learning process and it can be done both in a disciplinary and interdisciplinary manner depending on the topic. Vygotsky mentions that the teacher’s role is to be a facilitator and to provide scaffolding during all the stages, taking into consideration the concept of social constructivism (as cited by Adam, 2017). Additionally, the students enhance both academic and soft skills like group work and social interaction, (Dewi, 2017) states that students can develop some soft skills, such as creativity and authenticity. He also says that students are able to solve real life problems or answer questions based on their current situation, (Mapes, 2009) says that one feature of PBL is also that projects are nowadays considered as the core of a curriculum and the approach sticks to real-life topics.

PBL also presents some challenges. For instance, some students face challenges like technology when using technology to prepare the final project (Zafirov, 2013). Time is another challenge both for teachers and students, and it is essential to establish projects with a realistic, short timeline of a month or so (Win, 1995).

Steps to successfully apply PBL in the classroom

Parish (2019) in her research has identified some steps to apply PBL. First, the students select the topic or it can be suggested by the teacher, and the form of the artifact (final project) is determined by the students. Then they research the topic and do a schedule to develop the activities. After that, they edit the draft of the report, taking into consideration the type of audience. The artifact is presented in public and assessed by the teacher using a rubric and finally, the students carry out peer evaluation. This sequence has been confirmed by other authors, for example (Williams, 1998) and (Win, 1997).

Project-Based Learning and speaking sub-skills

English is an international language and the learners’ final aim is to be able to communicate with others (Riswandi, 2018), (Munawarah et al. 2018), state that speaking is basically one of the hardest skills to master when acquiring English as a Foreign Language. This might be due to the acquisition of some sub-skills such as fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar, all of which make the task more challenging.

They also refer to fluency as the way of conveying phrases that imply a message with no or little hesitation and it involves some phonological features (Jaramillo, 2019) states that when assessing pronunciation, it is important to take into account accent, rhythm and intonation. She also says that pronunciation can vary according to different contexts like culture, learners’ age and origin. Another speaking sub-skill is vocabulary, amount of words, necessary to be understood in different contexts (Anjarani et al. 2015).

Learning grammar rules is essential to form either simple or complex utterances when it comes to speak (Dewi, 2017) contends that PBL helps learners to develop some of these sub-skills and presentation skills since the students present a video, display or publish the final product to an audience, and the process requires the practicing of the sub-skills mentioned above.

Motivation

There is no single definition about motivation. For instance, the Merriam-Webster dictionary defines motivation as “a motivating force, stimulus, or influence” (Dornyei, 1994) argues that motivation is a combination of personal and social features which are responsible for human conduct, so learning a new language depends upon basically three components: the learner’s level, language level and the environment. Likewise, learning a foreign language requires the students to have a great amount of motivation since this will help them to acquire the language successfully (My et al. 2020). In short, motivation plays an essential role in the teaching-learning process and it is directly related to the learners’ desire to learn and the effort they exert to succeed or fail while wishing to achieve the established goals.

Project-Based Learning and motivation

In Project-Based Learning, motivation plays an important role; it leads learners to create projects by themselves. Such motivation can emerge, as mentioned before, either intrinsically or extrinsically the learner such as competitiveness, curiosity, or external rewards (Shin, 2018).

For (Masgoret & Gardner, 2003), motivation is directly related to a specific goal, aspiration or reinforcement. When students are asked to display their projects, they feel motivated since they are able to give solutions to real problems. The artifacts are concrete and can be presented to the public to display the students’ work and allow them to reflect on the whole process (Blumenfeld et al. 1991).

Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation in PBL

Intrinsic motivation is the drive that comes from oneself guided by an innate stimulus like curiosity or the pleasure of learning something. In some cases, intrinsic motivation is led by some innate rewards that force one to do any task or to accomplish any goal (Pucher et al. 2002). On the other hand (Delgado & Tamayo, 2016) insist that extrinsic motivation requires an external encouragement, and it depends on the environment, namely, money or any kind of rewards.

For instance, students tend to do something just for the marks they can get in class, not for the mere enjoyment of learning. Although both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation are essential in the classroom, the latter leads the students to a deeper understanding of the content due to the different types of activities related to develop a project (Pucher et al., 2002). In short, enhancing intrinsic motivation is important when working with PBL because if the students can decide on the project they will work on, their intrinsic motivation will be high.

Literature review

This section provides an account of previous studies carried out in recent years to show that PBL helps to practice speaking sub-skills and students’ motivation. (Rochmahwati, 2016) applied a quantitative design study by stages with 70 students of the English Department in Ponorogo, Indonesia using different instruments to gather data: questionnaires, tests, observations and interviews. The results showed that there was a significant effect of PBL on students’ speaking skills. Similarly, through an action research study conducted by (Ichsan et al. 2016) with 36 secondary school students through observations and quantitative data tools, the researchers found that after working with PBL, the oral performance, especially, fluency and accuracy of the participants increased.

Regarding motivation, (González et al. 2019) found a significant increase of motivation and confidence levels achieved after applying PBL with secondary school students in Colombia. Their results resemble a study conducted by (Roberton, 2011) with college students where the findings indicated that PBL helped enhance motivation at some stage with cooperative learning activities, (Ali & Henawy, 2015) conducted an action research project with 20 high school students from Port-Said in order to explore students’ attitudes towards the use of PBL when learning English, and the impact on speaking performance.

Results showed that PBL had a significant impact on students’ motivation; furthermore, the data revealed that there was a marked development of oral communication skills. (Piedra, 2021) found that although Project-Based Learning helps students to enhance cooperative learning as well as self-confidence and motivation in class, the findings revealed that there was not much improvement in speaking sub-skills.

As opposed to the research studies mentioned above about how PBL can help students’ motivation, (Edelson et al. 1999) found that PBL, apparently, does not improve motivation. The reasons might be the long steps students have to follow to do a project, including the setting of the inquiry question, gathering information, developing the project, and presenting it to the teacher.

All this can be stressful or demotivating. In the same vein, the findings of (Aldabbus’, 2018) showed that students faced various challenges, for example, looking for a relevant topic to work on, inadequate facilities, and time management, which made it difficult to accomplish PBL. However, the researcher suggested some recommendations to implement PBL successfully.

As it can be seen many researchers’ findings showed that PBL can help students to improve speaking sub-skills as well as their motivation; however, some results showed that on occasion students face various challenges that may demotivate them when carrying out their projects.

Design

Participants

The participants in the research study were 27 students of the second course of Bachillerato from Gabriel Cevallos Garcia public high school, who are from 15 to 16 years old and their mother tongue is Spanish. The participants were selected since the researcher is currently teaching English to them and also because they worked with interdisciplinary projects in virtual classes during the last academic year. Before starting the study, the researchers informed the participants about the purpose of the research. Also, they let students know that the data gathered would be kept confidential due to ethical considerations as suggested by (Creswell, 2008).

Data collection instruments and procedure

In order to explore what sub-skills the participants were able to practice with PBL, and to gather the quantitative data about the artifacts made by the participants a project was set up for the first term of the school year. Before explaining the instruments and the procedure, I would like to mention that the artifacts the students made were products that benefited their community such as houses made of carton for stray dogs, beds for a dog’s shelter, gardening products, and handmade soap. The students presented their artifacts via different digital tools like Power point presentations, Canva apps or videos.

The procedure followed the steps suggested by (Nguyen, 2011). The participants made their artifacts at home while they were in virtual classes. They set the inquiry question, and then they decided what the final product will be. Then they researched and organized the information. After that, they decided on the language to be used to display the artifact. The students presented the final products through videos and the teacher assessed them using a rubric as mentioned above. The researcher used an adapted rubric of the Ministry of Education (Ministerio de Educación, 2014) to assess fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar.

In addition, to collect the perceptions of secondary students regarding the use of PBL to practice speaking sub-skills, the researcher applied an online survey via Google forms with closed and open-ended questions. Furthermore, in order to gauge the perceptions of students and teachers about PBL to increase motivation, a structured interview was conducted with ten students and two teachers via Zoom sessions.

Data analysis

Quantitative data

The rubric data was organized in spreadsheets for later analysis with the statistical software SPSS 25 (Field, 2018). The rubric results were described using minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation measures. The data analysis shows that the components of the rubric did not have normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test). Therefore, a nonparametric test, called Kruskal Wallis, was conducted in order to prove the differences between the four components of the rubric (fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar). The statistic level adopted to answer the research questions was 0.05. In addition, an eta square (η²) was applied to establish the effect size.

Qualitative data

According to (Saldaña, 2009), patterns are several, repeated and relevant words that a researcher can find across the interviews. The qualitative data of this research study about the perceptions on motivation taken from the interviews was analyzed by the recognition of patterns such as motivation and enjoyment. The participants’ native language is Spanish, so the students were interviewed in Spanish to avoid misunderstanding of the questions. Then the answers were translated into English. Filep (2009) describes the previous process as “both tasks of conducting interviews and translating interview data in multilingual/multicultural settings represent complex situations, in which not only the language, but also the ‘culture’ has to be translated or ‘interpreted’ and dealt with” (p. 60).

RESULTS

The results are presented in two sections. The first one, which includes the quantitative data, is related to the exploration of four speaking sub-skills: fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. The second one refers to the qualitative analysis of students’ and teachers’ perceptions about using the PBL approach to increase motivation. The information of these two sections describes the application of the PBL approach on secondary students’ practicing speaking sub-skills and their perceptions about motivation.

Exploring speaking sub-skills using quantitative data

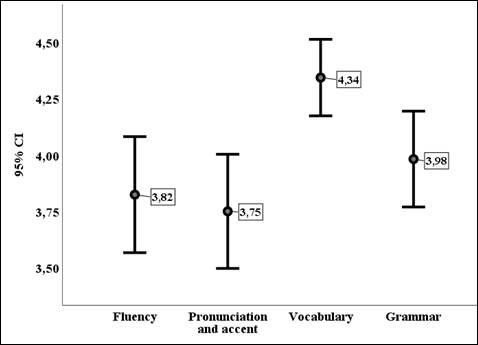

The results of the rubric scores allow exploring the speaking sub-skills that students practice through Project-Based Learning. Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation of each sub-skill. The highest oral sub-skill is vocabulary, which mean is 4.34 (SD 0.43). The lowest sub-skill is pronunciation followed by fluency with 3.75 (SD 0.64) and 3.82 (0.65) points in average, respectively.

Table 1

Mean and standard deviation of speaking sub-skills.

|

|

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

|

Fluency |

2.50 |

5.00 |

3.82 |

0.65 |

|

Pronunciation |

2.75 |

5.00 |

3.75 |

0.64 |

|

Vocabulary |

3.50 |

5.00 |

4.34 |

0.43 |

|

Grammar |

3.00 |

4.75 |

3.98 |

0.54 |

Source: Field research.

The Kruskal Wallis test was conducted to establish if there were significant differences among the components’ means (Kruskal Wallis (4df) =12.23; p=0,016; η²=0,088). The results reveal that there were some differences. In Figure 1 it can be seen that the highest component is vocabulary (5.00), which is significantly different from the two lowest: fluency and pronunciation.

Figure 1. Differences in speaking-sub-skills.

Source: Field research.

Students’ perceptions on speaking subskills

In order to explore the perceptions of secondary students regarding the use of PBL to practice fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar, the researchers administered an online survey with closed and open-ended questions and an interview. In the survey, there were four questions that identified the speaking sub-skills that students practiced when using PBL.

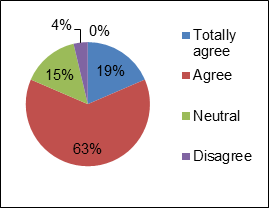

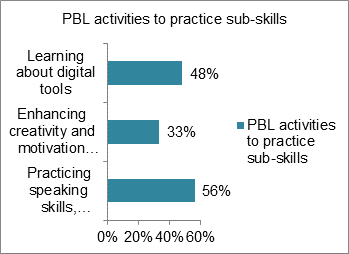

Figure 2.a shows the students’ perceptions about PBL activities. Most of the students totally agreed (19%) and agreed (63%) that the program helped them to improve speaking subs-kills (F2.a). Moreover, to identify which activity they perceived as the one that helped them the most, they could choose one or more options (F2.b). Most students selected the options that involved the practicing of speaking skills, the improvement of pronunciation, and an increase in vocabulary (56%). Another important option was learning about different tools (48%)

Figure 2.a. Students’ agreement about the help of PBL for improving speaking sub-skills.

Source: Field research.

Figure 2.b. Students’ perceptions about the most helpful activities to practice speaking sub-skills

Source: Field research.

The qualitative analysis of the interviews revealed which sub-skills the students felt they had improved with the aid of PBL. Most students argued that they basically increased fluency. Some of their testimonies highlighted this improvement as we can see in the next quotes. I think I started talking with greater confidence and ease since before I was afraid to say some things because I was afraid to be judged. But when I was forced to work with a computer or video, after practicing several times, I overcame these fears (Student A). It helped me in fluency because I learned to say a few sentences without the need to translate in my head (Student B).

Most of the students' responses were succinct, so they generally pointed out that they improved their level without specifying any oral aspect. For example, Student B said: “It helped me with oral expression, especially fluency.” Another student agreed with the general results presented in the previous section by stating that she acquired a wide range of vocabulary. “I think that I learned a lot of words I didn't know before, of course I had the need to translate, but they already stayed in my head” (Student C).

In summary, the students stated that they improved fluency; however, the results of the study do not show this sub-skill as the highest one, instead vocabulary is the highest one.

Students’ perceptions about motivation

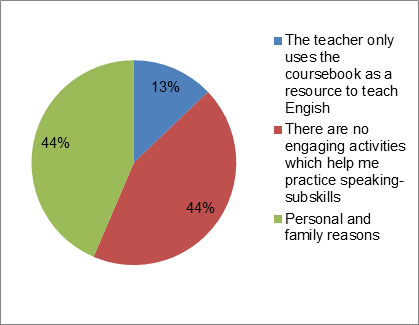

Some questions regarding the perceptions of the students on the use PBL to increase motivation were also asked in the survey. Figure 3 shows two graphs related to the reasons why students are demotivated in class. The main reasons of the students’ demotivation are that activities that are meant to help them to practice speaking skills are not engaging, 44%, and that they have personal and family issues (44%) (F3).

Figure 3. Students’ demotivation reasons.

Source: Field research

Teachers’ perceptions about motivation

Regarding teachers’ testimonies, they did not offer specifications about the sub-skills that can be improved with PBL. However, they argued that the benefits actually point to motivation in terms of interaction by using alternative methods. The paragraphs below illustrate some of the teachers’ perceptions:

As far as I know about PBL, I have realized that when they (the students) have a project to develop, they are forced to use the target language. The most important is that the students are able to communicate, although they do wrong sometimes, I guess. (Teacher A)

Sometimes the guys are tired of applying the same tools so they end up getting bored. It is important that the activities in class vary a little. For them, a project is a challenge to use English. The good news is that they can easily use internet programs since using the different digital resource is just a piece of cake. It must be exploited by giving them a little bit of freedom to undertake projects. Sometimes you don't even imagine the potential they have until you see the product of the project. (Teacher B)

The two teachers who were interviewed value using activities that students are not familiar with because the teachers encourage them to take advantage of their skills with technology. However, they noted the need to monitor students to ensure that they use English in their projects as Rongbutsri, Khalid, and Ryberg (2011) agree on the advantages of applying PBL.

DISCUSSION

Regarding the first research question about the exploration of speaking-subskills, the results in the study showed that the highest oral sub-skill that the 27 participants practiced through PBL was vocabulary. Even though the students stated in the interviews that they were able to improve fluency and pronunciation, the results do not show them as the highest ones. Similar results can be seen in the study conducted by (Piedra, 2021) with not much improvement in the speaking subskills fluency and pronunciation. This can be attributed to the several limitations the researcher has found like students’ absences to classes and lack of resources such as a computer or stable internet connection.

On the contrary to the present study’s results, through an action research study conducted by (Ichsan, 2016) with a similar sample, the researchers found that there was an improvement in fluency and accuracy after applying PBL in the classroom. In the same vein, the results of a research study by (Ali & Henawy, 2015) showed a notable improvement in oral communication skills.

In order to answer the second research question about motivation, the qualitative data showed that PBL helped improve participants’ motivation. The projects they made and presented helped the participants to foster self-confidence and autonomy. These results can be compared with the research by (González et al. 2019) which results show there was a marked increase on motivation and confidence levels.

CONCLUSION

The findings revealed that even though the students stated that they had improved their fluency, the results of the study did not show this sub-skill as the highest one. One of the reasons for this might be that when the students presented their projects, some of them read from their notes, either looking at what they have written on paper or what they had on the screen. Therefore, there are many challenges students face when working with PBL. One of them is the lack of knowledge of using technology to prepare the final project (Zafirov, 2013). Likewise, time is another challenge both for teachers and students, and it is essential to establish projects with a realistic, short timeline of a month or so (Win, 1995). In conclusion, Project-Based Learning helped students practice some speaking sub-skills such as fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar as well as motivation.

It is necessary to acknowledge the limitations of the study. First, the size of the sample (27 students and two teachers) implies that the generalizability of the findings is also limited. Also, some students did not have either computers or a stable internet connection needed to look for information about their project and to create a digital presentation or edit a video.

In order to find out if PBL can be a useful approach to enhance speaking sub-skills and motivation, one would need to carry out more research studies among high school students in a variety of contexts (e.g., urban and rural). It is more likely that teaching-learning will take place in hybrid and blended delivery forms and this may affect the way PBL projects are conducted.

No monetary assistance was involved in the project.

I would like to express my thanks to the students of the second course of Bachillerato for letting me use their artifacts. I would also like the thank Catholic University of Cuenca for letting me develop this research study helping me nurture my knowledge and widen my horizons.

REFERENCES CONSULTED

Adam, I. (2017). Vygotsky’s social constructivists theory of learning. Unpublished Research Paper. https://bit.ly/3J081yn

Aldabbus, S. (2018). Project-Based Learning: Implementation & challenges. International Journal of Education, Learning and Development. 6 (3), 71-79.

Ali, M. S., & El-Henawy, W. (2015). Using project-based learning for developing English oral performance: a learner-friendly model. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference. Faculty of Education, Port Said University (18-19). Retrived from https://n9.cl/pd5c2

Anjarani, S., Asib, A., & Sulistyawati, H. (2015). A correlational study between extroversion personality, vocabulary mastery, and speaking skill. English Education, 4(1), 49-55. doi:10.20961/eed.v4i1.34716

Bartscher, K., Goul, B., & Nutter, S. (1995). Increasing students motivation through Project-Based Learning. Master's dissertation, Saint Xavier University. Port-Said, Egypt Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED392549

Blumenfeld, P., Soloway, E., & Marx, R., Krajcik, S., Guzdial, M., Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating Projec-Based Learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26(3 & 4), 369-398. doi: 10.1080/00461520.1991.9653139

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, I(1), 1–47. doi:10.1093/applin/i.1.1

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Christchurch, New Zealand: Sage Publications.

Delgado, C.R., & Tamayo, C.B. (2016). Strategies of motivation in the teaching-learning process of the English language, Bachelor’s thesis, University of Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador. Retrieved from http://repositorio.ug.edu.ec/handle/redug/24679

Dewi, L. P. A. N. (2017). Improving speaking competency of the students at SMK N 4 Bangli using project-based learning. Journal of Education Action Research, 1(1), 40-48. doi:10.23887/jear.v1i1.10122

Dornyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the Foreign Language classroom. The modern language journal, 78 (3), 273-284. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02042.x

Edelson, D., Gordin, D., & Pea, R. (1999). Addressing the challenges of inquiry-based learning through technology and curriculum design. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 8(3), 391–450. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0803&4_3

Field, A. (2018). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics 5e + SPSS 24 (5th ed.). Christchurch, New Zealand: Sage Publications.

Filep, B. (2009). Interview and translation strategies: coping with multilingual settings and data. Social Geography, 4(1), 59–70. doi:10.5194/sg-4-59-2009

González, D., Córdoba, A., & Giraldo, A. (2019). The affective filter role in learning English as a Foreign Language through Project-Based method in high school students from a school in Colombia. Revista Boletin Redipe, 8, 153-167. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336700614

Grant, C., & Azadeh, O. (2014). Understanding, selecting, and integrating a theoretical framework in dissertation research: Creating the Blueprint for your house. Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, and Research, 4(2), 12-26. doi:10.1080/15391523.2005.10782450

Hernández, J. S., & Arturo, V. H. (2019). Strengthening oral production in English of students with basic level by means of Project-Based Learning, Bachelor’s thesis, Free Univesity of Colombia, Bogota, Colombia. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/10901/17715

Ichsan, M. H., Apriliaswati, R., & Apriliaswati, E. (2019). Improving students speaking skill through project-based learning. English Education Study Program, 6(2), 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.26418/jppk.v6i2.18718

Jaramillo, G. (2019). Project-Based Learning method to develop speaking skill in the students of eighth level of San Felipe Neri school. Master’s thesis. University Ambato. Ambato, Ecuador. http://repositorio.uta.edu.ec/jspui/handle/123456789/30430

Knoll, M. (1997). The project mehtod: Its vocational education origin and international development. Journal of Industrial Teacher Education, 34(3). https://bit.ly/3iY68HS

Kothari, C. (2004). Research Methodology-Methods and Techniques (Second Revised Edition). New Delhi: New Age International Publishers.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. New York: Phoenix Elt.

Leat, D. (2017). Enquiry and Project-Based Learning: students, schools and society. Routledge.

Mapes, M.R. (2009). Effects and challenges of Project- Based learning: A review. Master’s thesis. Northern Michigan University, Michigan, U.S.A. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/38eOk9n

Masgoret, A.M., & Gardner, R. C. (2003). Attitudes, motivation, and second language learning: A meta-analysis of studies conducted by Gardner and associates: Attitudes, motivation, and second language. Language Learning, 53(S1), 167–210. doi:10.1111/1467-9922.00227

Ministerio de Educación (2014). Classroom Assessment Suggestions. Retrieved from https://n9.cl/ebk6x

Ministerio de Educación (2014). National curriculum guidelines. Ministerio de Educación del Ecuador. Retrieved from https://n9.cl/low66

Munawarah, J., Kasim, U., & Daud, B. (2018). Improving speaking sub-skills by using the attention, relevance, confidence and satisfaction (ARCS) model. English Education Journal, 9, 356-376.

My, L. T., Hang, N. T., Thao, N. T., & Oanh, D. T. (2020). Integrating project-based learning (PBL) in EFL learning: An effective tool to enhance the students’ motivation. International Journal of Advanced Scientific, 5(11), 9-19. doi:10.36282/ijasrm/5.11.2020.1766

Nguyen, T.V.L. (2011). Project-based learning in teaching English as a foreign language. VNU Journal of Foreign Studies, 27(2), 140-146. https://js.vnu.edu.vn/FS/article/view/1476

Parrish, B. (2019). Teaching adult English language learners: A practical introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Piedra, K. D. (2021). Cooperative learning in PBL to develop speaking. Master’s thesis. Casa Grande University, Guayaquil, Ecuador. Retrieved from http://dspace.casagrande.edu.ec:8080/handle/ucasagrande/2690

Poonpon, K. (2017). Enhancing English Skills through Project-Based Learning. The English Teacher, 40, 1-10. https://n9.cl/omsh85

Pucher, R., Mense, A., & Wahl, H. (2002). How to motivate students in Project Based Learning. In IEEE AFRICON. 6th Africon Conference in Africa, pp. 443-446 vol.1, doi: 10.1109/AFRCON.2002.1146878.

Riswandi, D. (2018). The implementation of Project-Based Learning to improve student’s speaking skill. International Journal of Language Teaching and Education, 2 (1), 32-40. https://doi.org/10.22437/ijolte.v2i1.4609

Roberton, T. (2011). Reducing affective filter in adult English language learning classrooms. Master’s thesis, The Evergreen State College, Olympia, U.S.A. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3JZJ1ZC

Rochmahwati, P. (2016). Project-based learning to raise students’ speaking ability: its’ effect and implementation (a mix method research in speaking ii subject at Stain Ponorogo). Kodifi kasia, 9(1), 199-221. Doi: 10.21154/kodifikasia.v9i1.466

Saldaña, J. (2009). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Shaaban, K. A., & Ghaith, G. (2000). Student Motivation to Learn English as a Foreign Language. Foreign Language Annals, 33(6), 632–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2000.tb00932.x

Shin, M. H. (2018). Effects of Project-Based Learning on students’ motivation and self-efficacy. English Teaching, 73(1), 95-114. doi:10.15858/engtea.73.1.201803.95

Strong, M. (1984). Integrative motivation: Cause or result of successful second language acquisition? Language Learning, 34(3), 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1984.tb00339.x

Teague, R. (2000). Social constructivism & social studies. Retrieved from https://acortar.link/47tKVx

Williams, D.A. (1998). Documenting children’s learning: assesment and evaluation in the project approach. Master’s thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. Retrieved from https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca › PQDD_0001

Winn, S. (1995). Learning by doing: Teaching research methods through student participation in a commissioned research project. Studies in Higher Education, 20(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079512331381703

Yaman, I. (2014). EFL Students’ Attitudes towards the Development of Speaking Skills via Project-Based Learning: An Omnipresent Learning Perspective. Ph.D. Dissertation, Gazi University. https://doi.org/https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED577934

Zafirov, C. (2013). New challenges for the Project-Based learning. Trakia Journal of Sciences, 11(3), 298-302.

©2022 por los autores. Este artículo es de acceso abierto y distribuido según los términos y condiciones de la licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).